The Key to Compelling Communication

Much advice on public speaking and writing focuses on HOW to communicate but little on WHAT to communicate. This changed for me after I met my future business partner, who taught me a valuable lesson.

In this series of posts, I have been sharing lessons learned in my half century in enterprise IT. We left off with my founding, along with Dan Husiak, of the management consulting firm Strativa, and our acquisition of the IT research firm Computer Economics. I sold both firms in 2020 and retired from employment in 2024.

In this post, I want to share another important lesson I learned from Dan in thinking and communicating.

It’s What You Say, Not Just How You Say It

Most of the advice I see regarding public speaking focuses on style, for example, how to stand, modulate your voice, and gesture. There are tips on the use of humor and storytelling, engaging the audience, and how to field questions.

The same goes for written communications. For example, there is much advice on how to format slides with a good color scheme, the use of graphics, headings, and animation. For reports, there are tips on writing introductions and conclusions, using headings, subheadings, bulleted lists, and schematics.

In other words, in both speaking and writing, the focus is too often on HOW to communicate but little on WHAT to communicate. But effective communication flows from clear thinking. You need to have something compelling to say. Some of the best public speakers I’ve ever heard were not particularly polished, but they captured the audience through the clarity and power of their idea.

Throughout my career, people have told me that I have “strong written and verbal communication skills.” I write clearly, and I’m comfortable in front of an audience. But in the early years, it often took me too much time to decide what I wanted to say.

A Public Speaking Opportunity

This began to change in 1998 when I hired Dan during my time with the SI Firm. Shortly thereafter I had an opportunity to give a presentation to an APICS (now ASCM) chapter meeting. This was during the dot-com boom, and I wanted to use my talk as an opportunity to generate leads for our new e-business strategy consulting service.

I spent weeks pulling together information. I had growth statistics for the internet and e-commerce, the results of a user survey we did, and an analysis of emerging e-business models, opportunities and threats, and so forth—over 100 slides.

To move things forward I asked my team, including Dan, to let me walk them through some of the slides and give me feedback.

Dan didn’t say much. But I’ll never forget what he said at the end:

What’s your point?

I had no idea. So, I replied, “Well, it could be about this, or it could be that” referring to what I thought were some of the more interesting slides.

Then he said:

Frank, you’ve got a lot of material here. But you need to decide what it is that you want your audience to come away with. And you have to be able to say that in a sentence or two. Then everything else you share either leads up to that or explains it in more detail.

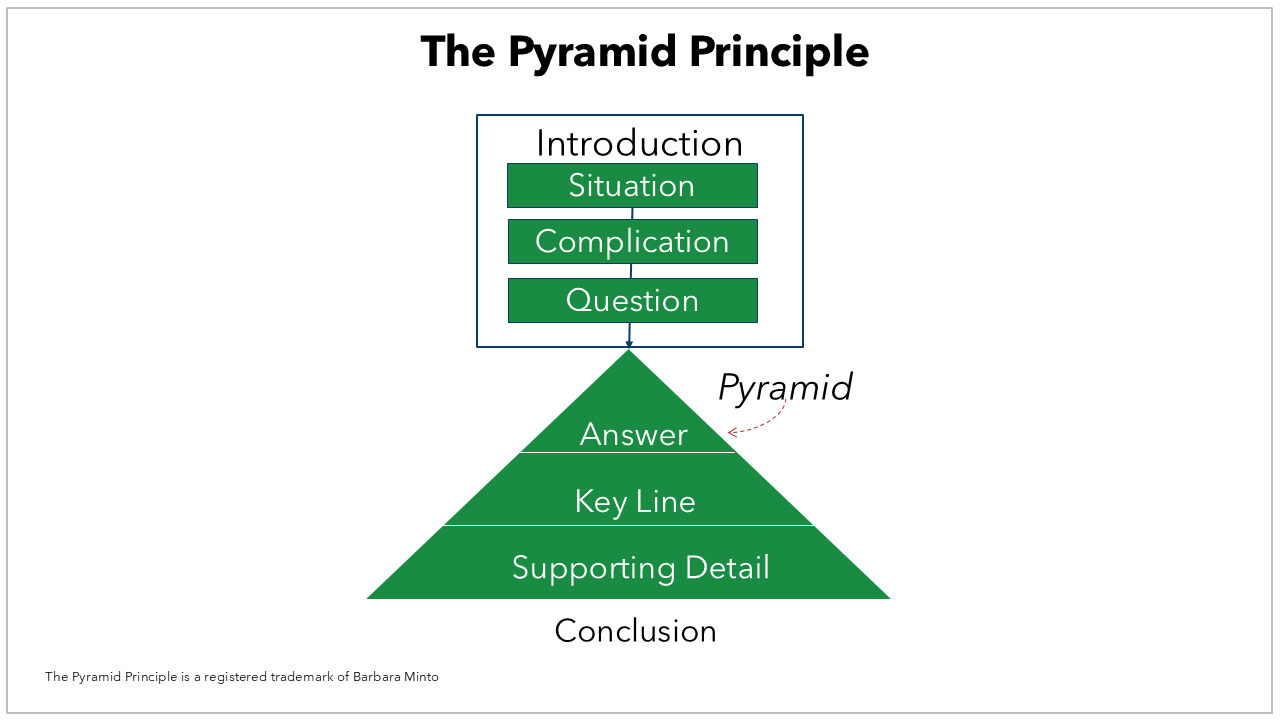

He then gave me a quick overview of something he called The Pyramid Principle [1]. He drew a diagram similar to this on the white board.

He explained:

The “Answer” is your main point. But you can’t just jump to the Answer. You need to set it up with a dramatic introduction. You start with a “Situation,” telling people something they will agree with, to set the stage. Then you bring in a “Complication,” for example, a new development, a problem, or a challenge. That leads to a “Question” in the mind of the audience that you then can answer with your main point.

Now, from what you said, your audience is mostly going to be traditional manufacturing people. Most of them barely have a website, and if they do, it’s just an online brochure about their company, with no e-commerce capability. At the same time, they are hearing all the hype about dot-coms like Amazon taking over. So, they are in a panic.

So your introduction could be something like this: Situation—we’ve all heard about the dot-com companies. They have a strategy to take over entire industries. Complication—But most of you do not work for dot-com companies. You are a traditional brick-and-mortar business. Question—So, what should you do? Answer—There needs to be an e-commerce strategy for the rest of us.

If that’s your Answer, then you need to decide on your key line. That will be to break down your answer. The key line could be things such as, the reasons why you need an e-commerce strategy, or the elements of a strategy, or the steps in developing such a strategy, or examples of traditional companies that have developed such a strategy.

So, now we had the start of a pyramid that looked like this:

Obviously, this pyramid was only a start, but it was enough to show me how to structure my thinking. I came back in a day or two and told Dan that I thought the best key line would be to outline the steps of the process to develop an e-business strategy. That would demonstrate that we had a framework to help clients with this. This would be the best approach to generate leads for our consulting services. Dan agreed, so I restructured my presentation around this pyramid.

The Pyramid Begins to Take Shape

Digging through my archives, I recently found my presentation slides, and I have now reverse-engineered the Pyramid, as shown below:

So, my talk track would go something like this:

As we all know, the use of the internet in business has been growing rapidly. [Here are some statistics.] And the web is a great technology for e-commerce. [Here’s why.]

Although you might feel like you are falling behind, it’s not too late. Most companies are still in the early stages. The impact will be even greater in the future. [Here’s why.]

So, if it’s not too late, what should you do?

I’m here to tell you that you need to develop your e-commerce strategy based on three dimensions: Your industry, your value chain, and the size of the potential benefits.

Industry opportunities and threats should drive how aggressive your strategy should be—whether the internet is a disruptive technology for your industry, an opportunity for a major lift in your business, or just giving you some incremental improvements.

Your value chain (your customers, suppliers, channels, and internal processes) should drive the choice of business initiatives for your e-commerce strategy.

Quantifying the potential benefits will tell you how much you should invest in e-commerce, that is, the business case.

Now, let me share with you how we go about each of these major steps and give you some examples of how we develop an e-commerce strategy. [Details and examples of our methodology.]

In conclusion [2], I recommend that once you have outlined your e-commerce strategy, put together a rapid proof of concept to get started quickly and then refine it based on what you learn with an early prototype.

The above summary does not do justice to the depth of the final presentation, which ran to nearly 50 slides. I’m amazed that I was able to deliver it in an hour.

Results of the Presentation

The beauty of this pyramid is that it wasn’t just a collection of interesting points about e-commerce. Rather, it showed the audience that we had a structured approach to developing an e-commerce strategy. I was showing them the methodology, with lots of examples. If anyone in the audience was looking for help, I wanted them to think, “I can see myself working with this guy.”

The presentation was a well received. I collected business cards from those who wanted a copy of the slides. One of those was Guilda Javaheri, an IT director at Seiko Instruments, USA and a member of Seiko’s IT steering committee.

A year later, based on this lead, Seiko became one of the first clients of our consulting firm, Strativa. Guilda brought us in to facilitate development of the firm’s e-business strategy, and we followed the methodology exactly as I had outlined in my presentation. Over the following decades, Guilda grew to become a CIO and a CTO at other firms, where she brought us in for other engagements.

A Bittersweet Postscript

Over the years, Dan and I made it a habit to train our consultants in the use of the Pyramid Principle. But the real learning came through practice, like I received with my APICS presentation.

We also included the training as part of our consulting engagements. We could deliver a one-hour version, or if the client was willing, a half day or a full day version. Team members then could apply it in whatever project we were working on but also in their careers generally. Eventually, I made it part of our educational offering on critical and creative thinking.

Then, when we acquired Computer Economics, I used it to train research analysts to help them become better thinkers and better writers. And when we were acquired by Avasant in 2000, my training became part of the firm’s new employee onboarding process.

The Pyramid Principle is not just for business communications. Dan loved to give everyday examples of using it to structure a simple email message, a phone call, or a conversation with a family member.

After Dan’s passing in 2008, I found out just how much he practiced what he preached. In cleaning out his desk I found notes to himself that included handwritten pyramids for conversations he’d had with me over the years. I remembered those conversations and marveled at his discipline in preparing for our meetings together.

End Notes

[1] The Pyramid Principle was developed by Barbara Minto, one of the first female professional at McKinsey. She was hired in 1963, right after receiving her MBA from Harvard Business School as one of the first women graduates. She soon moved into a position training new McKinsey consultants in how to write in the McKinsey way. She left McKinsey in 1973 and founded Minto International to deliver Pyramid Principle training to a wider audience. As a result, most major consulting firms today use the Pyramid Principle in some form or another. Her book, The Pyramid Principle, is available on Amazon. I have several copies and highly recommend it.

In writing this post, I found just one video of Barbara Minto, where she is interviewed in 2012 at some sort of social event. Take a couple minutes to watch it and see if you agree, she is quite delightful.

[2] In Minto’s training, she does not include a conclusion. I believe this is because her original audience was consultants, delivering findings or recommendations to clients. My view is that, in public speaking and many kinds of written communications, you need some sort of conclusion, even if it is just to restate the Answer, to ask your audience to approve your recommendation, or to outline next steps. In my training of the Pyramid Principle, I include a long list of ideas for writing a conclusion.

Like this post? Browse my past posts.

I’m not an IT person, but I really enjoyed reading this post. I’m a detailed person, even when conveying a story of something that happened. I like to start from the beginning detail which tends to lose people, while also taking a long time to get to my point. With this principle, I’ve learned to start with the bottom line and then fill in the details. This approach has kept my listener tuned in.